Click over Logo to return to Home Page

12 December 2006

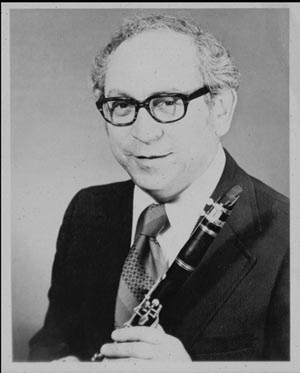

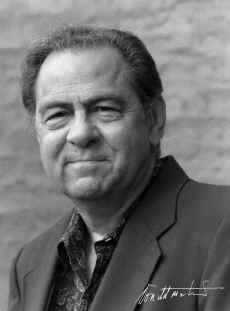

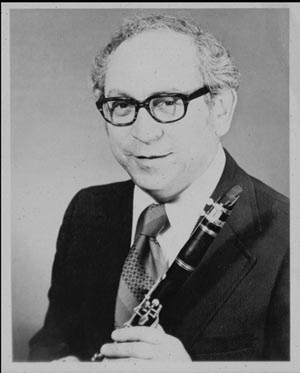

In Memoriam - Kenny Davern - Jazz Clarinetist

Sandia Park, New Mexico

John Kenneth Davern (born

January 7,

1935, died

December

12, 2006)

better known as Kenny Davern is one of the premier

jazz

clarinetists

of his generation. Kenny died of a heart attack at his Sandia Park, New Mexico

home.

He was born in

Huntington,

Long

Island to a family of mixed Jewish and Italian-Catholic ancestry. His

mothers family originally came from

Vienna,

Austria, were

his great-grandfather Alfred Roth had been a

colonel in

the

Austro-Hungarian

cavalry, the

highest rank accessible to a Jew in the

Habsburg

Imperial army.

After hearing

Pee Wee Russell the first time, he was convinced that he wanted to be a jazz

musician, too; and at the age of 16 he joined the musician's union, first as a

baritone saxophone player. In 1954 he joined

Jack Teagarden's Band, and after only a few days with the band he made his

first jazz recordings. Later on, he worked with bands lead by

Phil

Napoleon and

Pee Wee Erwin before joining the

Dukes of Dixieland in 1962. The late 1960s found him free-lancing with a.o.

Red Allen,

Ralph

Sutton,

Yank

Lawson and his life-long friend

Dick Wellstood.

At this time, he had also taken up the

soprano saxophone, and when a spontaneous coupling with fellow reedman

Bob Wilber

at Dick Gibson's Colorado Jazz Party turned out be a huge success, one of the

most important jazz groups of the 1970s, Soprano Summit, was born. Co-led

by Wilber and Davern, both switching between the

clarinet

and various

saxophones, during the next five years Soprano Summit enjoyed a very

successful string of record dates and concerts. When the group disbanded in

1979, Davern devoted himself to solely playing

clarinet,

preferring trio formats with

piano and

drums. His

collaboration with Bob Wilber was revived in 1991, the new group being called

Summit Reunion. Leading his own quartets since the 1990s, Davern has

preferred the

guitar to the

piano in his

rhythm section, employing guitarists

Bucky Pizzarelli,

Howard

Alden and

James Chirillo.

In 1997, he was inducted into the Jazz

Hall of

Fame at

Rutgers University, and in 2001 he received a honorary doctorate of music at

Hamilton College,

Clinton, New York. In addition to the jazz greats that inspired him, Kenny

Davern indicates classical clarinetist David Weber, principal solo clarinetist

with the

New York City Ballet Orchestra, as his most important teacher.

Although playing mainly in

traditional jazz and

swing

settings, his musical interests encompass a much broader range of styles. In

1978 he collaborated with avantgarde players

Steve Lacy,

Steve

Swallow and

Paul

Motian on a

free jazz-inspired

album appropriately entitled Unexpected. In addition to his

accomplishments in jazz, his ardour and knowledge of

classical music is encyclopaedic, particularly of the work of conductor

Wilhelm Furtwängler.

Especially since he has been concentrating on exclusively playing the

clarinet,

Kenny Davern has been calling his own an unmatched mastery of the instrument. A

full, rounded tone, especially "woody" in the lower

chalumeau

register, combined with highly personal tone inflections and the ability to hit

notes far above the conventional range of the

clarinet,

have made his sound immediately recognizable. In the late 1980s, the

New

York Times hailed him as 'the finest jazz clarinetist playing today'.

26 September 2006

|

|

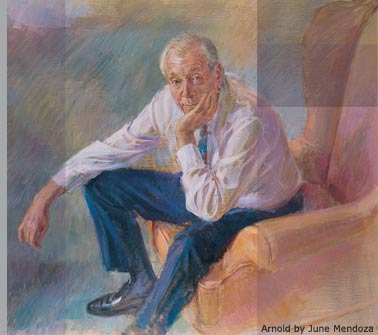

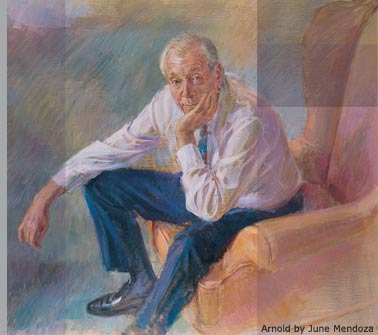

Sir Malcolm Arnold was most famous for his film scores

|

British composer Sir Malcolm Arnold has died in hospital after a brief

illness at the age of 84.

Sir Malcolm, who won an Oscar for the musical score to the Bridge on the

River Kwai film in 1958, was suffering from a chest infection. He is most

famous for his film scores, composing 132 including Whistle Down the Wind

and Hobson's Choice.

Sir Malcolm, who lived near Norwich, also composed seven ballets, nine

symphonies and two operas.

Sir Malcolm, one of the most famous composers of the 20th Century, leaves

behind two sons and one daughter. He died at the Norfolk and Norwich

Hospital.

|

Sir Malcolm, you could be responsible for my lifelong love of

real music

Sir Malcolm, you could be responsible for my lifelong love of

real music

|

Anthony Day, his companion and carer for the last 23 years, praised Sir

Malcolm as "the most wonderful man".

"People didn't see the man that I knew because he had frontal lobe

dementia over the last few years which slowly developed but, being with him,

he was a happy, lovely man who enjoyed his music and enjoyed his life," he

told BBC News.

Mr Day also paid tribute to Sir Malcolm's achievement in winning an Oscar

for Bridge on the River Kwai.

"They couldn't find anybody else to do the music in time because they

wanted to release it to the Oscars," Mr Day said.

"They gave him 10 days and he managed to write the complete score in 10

days."

|

He was a happy, lovely man who enjoyed his music and enjoyed his

life

He was a happy, lovely man who enjoyed his music and enjoyed his

life

|

Cellist Julian Lloyd Webber described Sir Malcolm as a "genius" who was

never entirely appreciated.

He said: "I think he was a very, very great composer but uneven in his

output.

"Because he had humour in his music he was never fully appreciated by the

classical establishment."

Lord Attenborough, the director and actor, said Sir Malcolm was a

"totally outstanding composer".

Sir Malcolm's music continues to be performed and recorded extensively by

leading orchestras both nationally and internationally.

He was awarded the CBE in 1970.

Saturday night was the premier of his version of the Three Musketeers at

the Alhambra in Bradford.

The performance, which was dedicated to him, went ahead as planned

Tributes:

I am a clarinettist who has played some of Malcolm Arnold's work ...

which is some of the most challenging and yet most rewarding I have worked

on. He was a great composer and knew my instrument well.

Eleanor Smith, Edinburgh

As one of Malcolm's biographers I got to know him very well in his final

years. In spite of his shameful treatment by the music critics who berated

him for being popular, he lived to see virtually all of his output recorded

and what is more selling well! More than any other composer I have known,

the music was the man. He may no longer be with us but listen to his music

to know what we have lost.

Paul RW Jackson, Winchester, Hampshire

Malcolm Arnold was one of the greatest symphonists that this country has

been fortunate to have had. He combined excellent technique with a vast

amount of humour (humour is a difficult object to achieve in music, unless

one wishes to indulge in pure pastiche), to create symphonies and other

works that will last. Arnolds technique included extremely subtle tonality

and key-play within this framework, along with highly original orchestration

that is challenging to play (I played French Horn in amateur orchestras and

brass bands, and have played in some of Arnolds works). The humour, I feel,

was not an attempt to cock a snook at the musical Establishment, rather it

was an expression of a man, a vital man and an insouciant man, confident in

his own abilities and not one who fawned on approval, who lived, breathed

and sweated music, and was not worried if the sweat produced a bit of a

stink.

Steve Robey, Harwich UK

A composer of great courage, who stuck to his principles despite the

fashionable barrage of atonality. Of composers born in the 1920's, virtually

all gave in to the pressure of the establishment. Malcolm Arnold stood firm,

and he alone kept the flame of classical music alive until a younger

generation came along to breathe new life into the genre once more. Good

though his film music is, his concert music is his real contribution. Among

many works, maybe the Second and fifth Symphonies stand out, together with

many of the concertos. He paid a terrible price for standing firm against

the tyranny of the establishment, but all who care about serious music

should be grateful to him for helping contemporary serious music to survive

to our day.

Michael Holley, Goring on Thames, Reading, UK

Sir Malcolm was a unique voice in dramatic and concert work, with a

distinctive bittersweet yet tingling way with his harmony and orchestration.

He was a great musical satirist and educator too, a tonal 'people's

composer' who nonetheless never dumbed-down. He also weathered the vortex of

many personal challenges in his inner and outer life. His music increasingly

appeals and will continue to do so, no doubt outlasting the canards of a

musical establishment who frequently underrated him.

William McCrum, Templepatrick, N. Ireland

When I read the news I took the score for the Symphony No.6 from my

shelf, the first major score by Malcolm Arnold I ever studied, which I still

regard fondly. In America, his legacy will certainly be kept alive in his

marvellous compositions for wind ensemble, whose orchestrations never cease

to amaze. He will be missed.

Bill Sisson, Onalaska, Wisconsin, United States

I became enamoured of Sir Malcolm's music when in college in Wisconsin in

the early 1980s. I was classical music director of the local 10 watt radio

station, and a couple who were patrons and supplemented our meagre budget

had me over to listen to their $20,000 system at various times. It was on

one of those occasions that I heard my first Lyrita recording. It was

Malcolm Arnold's "Dances," and after that I bought every recording of his

works I could lay my hands on, and I was never disappointed. He may not have

been as well known or widely appreciated by Americans in general, but among

those of us who appreciate the wonders of 20th Century British Classical,

his name has always been a standout. He will be missed.

Victor Davis, Napa, California, USA

"Four Cornish Dances" - Shivers down me spine - Especially the march

where it pictures walking down to the chapel on a Sunday morn, Methodist

style with the sea in the background and a pint of cider waiting at the

bar... In fact all of his dances.... Genius...

Gaz, Manchester

Anyone who has ever watched What the Papers Say on TV will be familiar

with his suite of English Dances.

Kevin, Liverpool

An extremely fine craftsman of music who suffered unjustified neglect

during this life. Time will tell whether it is Arnold's music or that of his

Serialist detractors that continues to be played and enjoyed by the public.

A crime that he wasn't celebrated and better commissioned - the BBC and Arts

Council should hang their heads in shame.

Matthew Woolhouse, Cambridge

One of the last true links with what most people think of as

'Englishness' in music is gone. And with him a great artist, much

misunderstood and maligned by the progressive musical establishments of the

day during his lifetime. I think of him as the John Betjeman of British

music, a people's composer, one with total integrity, originality and

professionalism, and to those who take the trouble of exploring his music

more deeply will be revealed unmistakeable genius.

Adrian Williams, Hereford, England

Now at last he will get the recognition from the serious music community

he certainly deserved.

Daniel Robinson, London

I am a member of the Birmingham Philharmonic Orchestra, of whom Sir

Malcolm Arnold is the patron. We performed a concert entirely comprising the

works of Arnold earlier this year to celebrate his 85th birthday. We are

also to perform Peterloo overture and A Grand Grand Festival Overture

amongst other pieces at a charity concert at Symphony Hall this coming

Wednesday 27th September. Personally I love playing Arnold's music and feel

that his passing will be greatly felt in our orchestra.

Jo Stubbs, Birmingham, West Midlands

Though we mourn the very sad loss of Sir Malcolm today we must celebrate,

the unique and wonderful legacy of his music left to us. Sir Malcolm touched

everyone who listened to his music, as he wrote in a very personal yet

public manner. Never, ever frightened of writing a 'good tune', his music

was full of his humanity, warmth and most importantly fun. We should be all

very thankful that Sir Malcolm was given to us and we must all celebrate his

birthday this year as he would have wanted with lots of concerts of his

wonderful music. God bless Sir Malcolm and many, many thanks to Anthony Day

for his untiring help and support to Sir Malcolm in his last years.

Lawrie Dunn, Burnham on Sea, Somerset

A true gent of music who has left a great legacy. From wonderful film

music to the inspired Guitar Concerto he will be sadly missed but forever

remembered.

John Elliott, York, Uk

Sir Malcolm Arnold was president of Rochdale Youth Orchestra, and until

they left to go to university, my two youngest daughters played in it for

several years. I was always impressed that Sir Malcolm took on the patronage

of what would seem to many to be an insignificant, small town orchestra. He

attended many concerts in spite of age and failing health, and that never

failed to impress me, that a world renowned musician and composer would take

the trouble to do that. I think that he was an innovative and interesting

composer, and I am sorry to hear of his passing.

Sonia Wilson, Rochdale, England

One of my fondest memories of the Proms was of Malcolm Arnold conducting

Britten's Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra. He was almost bent double

coaxing the most out of the orchestra - no mean feat for a man of his

physique - and clearly having a wonderful time himself. As, indeed, were we

Prommers!

David Brooks, Redmond, WA, 98053

I was fortunate enough to meet Malcolm Arnold a number of years' ago when

the BBC Philharmonic were performing some of his works. I remember his

almost equal pride over his extremely "loud" ties and the fact that few

critics had noticed that a movement in his (I think) sixth symphony had been

composed in strict serialist mode. A warm, witty and funny man who leaves an

astonishing and under-rated body of work. Though his film scores were

wonderful, we should not forget the quality of his concert music.

Steve Rouse, Manchester, England

I am a supporter/staff member of Rochdale Youth Orchestra, of which Sir

Malcolm was the president. We are sorry to hear of his passing.

Sian, Rochdale, Lancs

|

21 February 2006

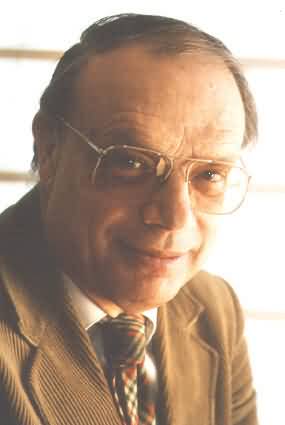

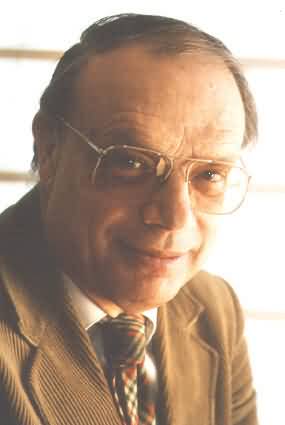

Sir Nicholas Shackleton - In Memoriam

Edinbirgh, United Kingdom

With the recent death of

Sir Nicholas Shackleton, paleoclimatology lost one of its brightest

pioneers. Over the last ~40 years, Nick made numerous far-reaching

contributions to our understanding of how climates varied in the past, and

through those studies, he identified factors that are critically important

for climate variability in the future. His career neatly encompasses the

birth of the new science of paleoceanography to its synthesis into the even

newer science of 'Earth Systems'; he made major contributions to these

evolving fields throughout his life, and his insightful papers are required

reading for students of paleoclimatology.

Fundamentally, Nick was a geologist, with a research focus on changes

in ocean chemistry recorded in the marine sediments and the calcium

carbonate shells of tiny organisms (foraminifera) commonly found in them.

Nick was among the first to recognize that changes in the oxygen isotope

ratio(18O/16O) was not simply a function of

temperature, as had been previously thought, but rather a reflection of

global scale ocean chemistry which changed as ice built up on the continents

during glaciations. This resulted from the fractionation of oxygen isotopes

in water molecules, following evaporation from the ocean surface. As water

vapor is carried towards higher latitudes, and condensation occurs, the

precipitation that forms contains more of the heavy isotope (18O)

which is thus returned to the ocean, leaving the vapor isotopically lighter.

When precipitation forms as snow, and remains on the continents to form ice

sheets, the overall composition of the world ocean gradually changes,

becoming isotopically heavier (enriched in 18O) compared to

periods when there are no ice sheets on the continents.

Benthic foraminifera (those forams living in the deep ocean where

temperatures change very little) incorporated the isotopically heavier water

into their structure as they formed their shells. Thus, by measuring the

oxygen isotope ratios in benthic foraminifera, Shackleton effectively had a

measure of how much ice had accumulated on landa paleoglaciation index.

Furthermore, because the deep ocean composition is fairly well mixed,

benthic forams from all parts of the ocean recorded these changes more or

less synchronously. Thus, the variations could be used to correlate marine

records wherever they were recovered, providing a universal index of past

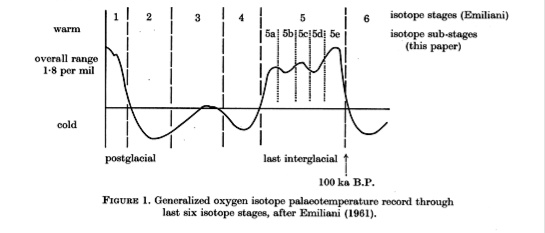

earth history. Variations in the oxygen isotopes gave rise to what are now

termed marine isotope stages; we are currently in isotope stage 1 (the

Holocene) and the last glaciation is represented by isotope stage 2 (when

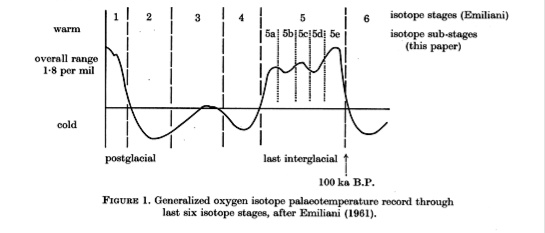

the world ocean was more enriched in the heavy isotope). Notably, Shackleton

(1969) was the first to make the (correct) identification of 'isotope stage

5e' with the Eemian interglacial identified in land-based pollen records

(see figure). At that time (~125,000 years ago), the isotopic composition of

the ocean indicated there was even less ice on the continents than there is

today. This corresponded to higher sea-levels (~6m higher than today)

largely because the Greenland ice sheet was much diminished. (It is now

thought that there was a much smaller ice cap on the island at the peak of

the last interglacial; these changes were brought about by orbital

variations, whereas today there are concerns that higher levels of

greenhouse gases may have a similar result).

Figure 1 from Shackleton (1969) showing the breakdown of the last

120,000 years into isotopic 'stages'.

Earlier stages show the slowly evolving nature of glaciation (and the

intervening interglacials) on the earth. Nick teamed up with Neil Opdyke, a

paleomagnetist who was able to recognize (and date) reversals of the earths

magnetic field, to provide a timescale for these changes in oxygen isotopes,

and this provided a chronology that could then be used to understand the

frequency of glaciations and rates of change. Once a fairly reliable

timescale was established, it soon became apparent that there had been

regular sequences of glaciations and interglaciations that were related to

orbital forcing (changes in the earths position in relation to the sun, as

elaborated by Milankovitch). This was described in a landmark paper in

Science (1976) Variations in the earths orbit: pacemaker of the ice ages,

co-authored with colleagues Jim Hays and John Imbrie. From this many more

studies of orbital forcing, extending far back beyond the Quaternary period

also evolved from the marine oxygen isotope stratigraphy. In particular, the

CLIMAP (1981) project emerged, in which paleoceanographers mapped ocean

conditions at the height of the last glaciation, by identifying in each

sediment core the position where the isotopes in benthic forams were most

enriched (indicating maximum ice on the continents). While many of the

initial CLIMAP conclusions have been substantially revised, Shackleton's

isotope chronology remains as an essential tool in understanding earth

history.

Having identified a universal chronometer for continental glaciationnot

in the moraines and outwash deposits that provide the direct evidence of

former ice sheets, but far away in the deep ocean basinsresearchers were

then able to better understand the history of other terrestrial records,

such as the vast loess (wind-blown silt) deposits of China, and the emerging

ice core records from Antarctica and Greenland. Furthermore, since the

isotopic record in the oceans registered ice growth and decay on land, it

effectively provided a proxy for sea-level changes that could be checked

with sea-level terraces from areas where the land had risen (such as on the

Huon Peninsula of New Guinea, and in Barbados), preserving a record of past

sea-level changes in the coral reefs now exposed on land. By comparing the

reef-based sea-level history with the benthic foram-based record, Shackleton

(with colleagues John Chappell and others) was able to assess the extent to

which deep ocean temperatures may have changed over time, which would have

confounded the simple paleoglaciation index he originally formulated.

Shackleton subsequently argued that changes in glaciation could not be fully

explained by orbital forcing, and that feedbacks involving carbon dioxide

must have played a critical role, thereby highlighting the importance of

changes in the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, in the

past and in the future.

Nick Shackletons research, arising from his original Ph.D. thesis on

isotopic variations of tiny marine organisms, had an enormous impact on

earth sciences. He had the insight to understand the implications of his

measurements and they literally transformed how we now view earth history.

For his discoveries he received many honors and awards. He was a Fellow of

the Royal Society, a Foreign Member of the U.S. Academy of Sciences, a

Fellow of the American Geophysical Union, and numerous other societies also

honored him. He was knighted for his services to science; with Willi

Dansgaard (who made similarly far-reaching studies of oxygen isotopes in

precipitation and applied these to ice cores) he received the Crafoord Prize

(considered as earth sciences Nobel Prize); he was also awarded Japans

Blue Planet Prize, the Milankovitch Medal, and most recently the Vetlesen

Prize.

Though he always considered himself, just a geologist, Nick had many

other talents, most notably in music. He was an

accomplished clarinet player and had a passionate interest in the history of

that instrument. He was considered a world expert for his knowledge of

antique clarinets and he had his own unique collection. At Cambridge

University, where he spent his entire career, Nick gave lectures on

Quaternary geology and paleoclimatology, but he also taught the physics of

music. Perhaps it was his knowledge of harmonics that played a critical role

in his understanding of orbital forcing and its impact on earth history. At

the tri-ennial ICP conference, Nick would always organise a Paleo-musicology

concert where the many musically talented scientists (and occasionally their

more-talented children) would entertain the rest of us. Nick was a true

Renaissance man and he leaves a very important legacy to both musicology and

the earth sciences. Besides all this, he was a nice guy and an inspiration

to all who came into contact with him.

14 February 2006

In Memoriam - Hans Olof Wickman ( Putte

Wickman) Jazz Clarinet Legend in Sweden

Stockholm, Sweden

Hans Olof Wickman, better known as Putte Wickman, born September 10, 1924

in Falun Kristine Assembly, Falun, February 14, 2006 in Grycksbo, Falun

Municipality, was a Swedish musician and clarinetist, especially in jazz. He

was self-taught clarinet player, which did not prevent that he was regarded

as one of the best in the world.

Wickman grew up in Big Tuna outside Borlänge. After secondary studies in

Stockholm in 1944, he was a summer in Hasse Kahn orchestra. Later in the

1940s he started his own sextet, which played Benny Goodman-jazz but also

more modern music. This sextet was up to the mid-1960s.

In recent years, did Wickman, but are not believers, church concerts with

guitarist Goran Fristorp and pianist Jan Lundgren. In 2004 he participated

in the tribute show, A tribute to Putte, held on the occasion of his 80th

birthday, with, among others, Povel Ramel, Svante Thuresson, Jan Lundgren,

Anders Berglund's big band. In 2005 he appeared on the Jazz Festival in

Norrtälje, and on tour Wickman Wanner, together with Anders Berglund big

band with, among others, Sheeba, and Jill Johnson as a singer.

Putte Wickman was one of the

few in the world forward, who played jazz on the clarinet. His game can not

be compared with Benny Goodman or Artie Shaw, for he created his own way to

play the return to traditional modern jazz on. Had it not been for so had

Putte Wickman clarinet existence of jazz never really existed. Putte Wickman

is one of the greatest jazz clarinetist of all time and we will all remember

him in a very long time to come

23 January 2006

David Weber In Memoriam

New York City USA

By DANIEL J. WAKIN

Published:

January 26, 2006

David Weber, a

clarinetist, who was one of the last remaining links to the pioneers of American

woodwind-playing and went on to become a master teacher, died on Monday at

Beth Israel Medical

Center in Manhattan. He was 92.

His son Michael Weber

announced the death. He had continued giving lessons until June.

Mr. Weber played for

conductors likeToscanini, Stokowski and Leinsdorf. His students occupy chairs in

orchestras around the country, including the

Milwaukee Symphony, the

Dallas Symphony and the Cleveland Orchestra. Benny Goodman took lessons (but

never paid and took his best reeds, Mr. Weber once said), and so did the jazz

clarinetist Kenny Davern.

But his most profound

influence may have been on the sound of the instrument.

Mr. Weber's great gift,

and his constant goal for students, was beauty of tone. His sound was full,

rich, resonant and pure.

"It had a unique bell-like

quality, that kind of clarity," said Jon Manasse, a soloist and principal

clarinetist of American Ballet Theater. "The resonance of the sound, when it was

correct, was enough to communicate the music without adding special effects or

gimmicks."

As recounted by Mr.

Manasse, Stokowski once called Mr. Weber over and said: "You, sir. Your tone,

it's like a dove cooing."

Mr. Weber himself, in an

article in The Clarinet, described good tone this way: "Think of colors: it's

got to be gold, silver, blue velvet. You have to reach out and touch it."

Mr. Weber was a dogmatic

teacher but deeply devoted to his students, and did not suffer fools gladly. He

had a reputation for being contentious, standing up to conductors and sometimes

alienating colleagues. He once argued with the conductor Bruno Walter, who tried

to make peace by giving an inscribed copy of his book about Mahler.

"I don't think it

succeeded," his son Michael said. "My father never spoke well of Bruno Walter in

my hearing." His survivors also include another son, Robert, and his wife,

Dorothy.

David Weber was born on

Dec. 18, 1913, in

Vilnius, Lithuania,

and moved with his family to Detroit. He took up the clarinet and studied with a

member of the Detroit Symphony. One day he arrived for a lesson and was sent

home; his teacher had committed suicide. The incident was searing, he told The

Clarinet.

He went to New York to

study with Simeon Bellison, the Russian principal clarinet of the New York

Philharmonic, who along with Daniel Bonade of France another Weber teacher

helped establish modern clarinet-playing in the United States.

In the late 1930's, he

auditioned for Toscanini and was immediately brought into the NBC Symphony. He

also had stints with the

New York Philharmonic,

Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, CBS Symphony and Symphony of the Air, the NBC

Symphony's successor. He was principal clarinet of the New York City Ballet

Orchestra from 1964 until 1986, when he retired from performance, and taught at

the Juilliard School.

8 December 2005

In Memoriam - Donald Martino, noted American composer

Newton, Massachusetts, USA

DONALD MARTINO (1931 -

2005) : Born in Plainfield, New Jersey, May 16, 1931, he began music lessons at

nine learning to play the clarinet, saxophone, and oboe and started

composing at 15. He holds degrees from Syracuse and Princeton Universities. A

member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a fellow of the American

Academy of Arts and Sciences, his many awards include two Fulbright

scholarships; three Guggenheim awards; grants from the Massachusetts Arts

Council, the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and the National Endowment

for the Arts; the Brandeis Creative Arts Citation in Music; the 1974 Pulitzer

Prize in music for his chamber work Notturno, First Prize in the 1985 Kennedy

Center Friedheim Competition for his String Quartet (1983), and most recently,

the Boston Symphony's Mark M. Horblit Award. Mr. Martino has taught at The Third

Street Music School Settlement in New York, Princeton, Yale, The New England

Conservatory of Music, where he was chairman of the composition department from

1969-1979, Brandeis, where he was Irving Fine Professor of Music, and Harvard,

where he is the Walter Bigelow Rosen Professor of Music, Emeritus. He has been

active as guest lecturer and has been Composer-in-Residence at Tanglewood, The

Composer's Conference, The Yale Summer School of Music and Art, The Pontino

Festival (It.), May in Miami, The Atlantic Center for the Arts, The Warebrook

Festival, The Ernest Bloch Festival, The Festival Internacional de Musica de

Morelia (Mex.), and has been Distinguished Visiting Professor at many

institutions of higher learning. Commissions for new works have come from,

among others, the Paderewski Fund; the Fromm, Naumburg, Koussevitzky, and

Coolidge Foundations; the Chicago, Boston, and San Francisco Symphonies; and a

number of musical societies and organizations. According to the New Grove,

"Martino's music has been characterized as expansive, dense, lucid, dramatic,

romantic, all of which are applicable. But it is his ability...to conjure up for

the listener a world of palpable presences and conceptions...that seems most

remarkable."

"Donald Martino, the Pulitzer Prize-winning American composer widely

respected for atonal works that combine intellectual rigor with

expressive freedom, died on Thursday aboard a cruise ship in the

Caribbean en route to Antigua. He was 74. During this trip, Mr Martino

was actively involved in composing a work for Violin and 14 Instruments

to the very day of his passing for the Tanglewood Music Center.

The cause was cardiac arrest following complications of diabetes, said

Lora Martino, his wife of 36 years, who was vacationing with him. Mr.

Martino lived in Newton, Mass.

A student of Roger Sessions and Milton Babbitt, he was an unapologetic

Modernist steeped in 12-tone techniques. His works, typically, were

dense and formidably complex. A skilled craftsman and comprehensive

musician, he believed in challenging listeners. In moments of

frustration, he attributed the difficulties his music had in winning

mainstream acceptance to concert promoters who cultivated a

"potty-trained audience," as he put it in an interview for his 60th

birthday.

For Clarinetists, he is well known for compositions such as his Set for

Solo Clarinet, and his Triple Clarinet Concerto, for Contemporary Ensemble.

His music publishing firm Dantalian, has a complete catalog of his works.

PUBLIC MEMORIAL and

TRIBUTE CONCERTS

A

public memorial to celebrate the life and music of Mr. Martino will be held on

March 19, 2006 at 3:00

p.m. at Paine Hall, Harvard University. Selections of his music will be

performed, as will other pieces dear to the composer. Family, friends, and

colleagues will also speak briefly and share remembrances.

A

public memorial to celebrate the life and music of Mr. Martino will be held on

March 19, 2006 at 3:00

p.m. at Paine Hall, Harvard University. Selections of his music will be

performed, as will other pieces dear to the composer. Family, friends, and

colleagues will also speak briefly and share remembrances.

For directions and information on free

parking, visit Harvard University's

Paine Hall Directions website or email

loramartino@verizon.net.

Please Note:

In honor of Donald Martino, an annual award will be given to a composition

student at the

New England Conservatory, where Mr. Martino was chairman of the Composition

department from 1969 - 1981. Memorial donations to fund this award may be sent

to:

New England Conservatory

Attn: Regina

Tracy

Development Office

290 Huntington Ave.

Boston, MA 02115

Please indicate "for Donald Martino prize"

when sending donations. For more details, contact Regina Tracy at (617)

585-1138 or Jennifer Hill at (617) 585-1169.

|

|

|

|

Josef Horak with Bass Clarinet colleague

|

|

|

|

Josef Horak, wife and Mike Getzin in Duesseldorf, Germany

|

|

|

|

World Bass Clarinet Convention

|

|

|

|

Horak on Bass Clarinet

|

|

|

23 November 2005

In Memoriam Josef Horak

It is very sad to report the passing of this great pioneer of the Bass

Clarinet, who just had a Festival held in honor of his legacy in Rotterdam,

Holland this month. This Convention honored the 50th Anniversary of a Bass

Clarinet Recital held at the beginning of this era. More information below about

Horak's illustrious solo career and his influence on the entire Bass Clarinet

world.

In March 1955, Josef Horák performed the world's first solo bass clarinet

recital.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of this great occasion the newly

founded World Bass Clarinet Foundation held a 3 day bass clarinet convention

from 21st-23rd October 2005 - the first event ever to

focus solely on all aspects of bass clarinet performance.

Historical

Event

On 23rd March 1955

the Czech bass clarinettist, Josef Horák, performed the first ever solo bass

clarinet recital. This recital marked a turning point for the bass clarinet and

provided me with the inspiration to organize the first World Bass Clarinet

Convention in the 50th anniversary year. - Henri Bok

|

The DUE BOEMI DI PRAGA was founded in 1963.

It is the only ensemble of that kind that has systematically

concentrated on the interpretations of music ranging from the

Renaissance up to the present times. By this art activity the two

Czech outstanding musicians have provoked a completly new sphere of

music literature which has not existed up to their time.

Leading world composers, as e.g. Paul Hindemith, Bohuslav Martinů,

Olivier Messiaen, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Frank Martin, Klaus Huber,

Henri Pousseur, Kazuo Fukushima, Pablo Casals or Alois Hába

dedicated or authorised their compositions to DUE BOEMI DI PRAGA.

In 1955, Josef Horák revealed to musicians and audiences who

uplifted this instrument from the orchestral ranks to the level of a

solo instrument. Its soft singing tone has become a new sound ideal

of the bass clarinet. The new starting and breathing technique has

broadened its extent, its dynamic scale as well as possibilities of

expression and technique. Horák has influenced the developmend of

the bass clarinet playing in the world by this decisive way.

Therefore world critics call him "Paganini of the bass clarinet".

His first evening concert in 1955 was at the same time the first

bass clarinet recital in the history of music. |

|

|

UNESCO - March 1988 - International Kolloquium

Festival Leo Janáček - Paris

|

Due Boemi made radio

recordings for 42 radio studios in Europe and overseas.

Due Boemi played concerts on 4 continents. |

|

|

We can find in the

repertoire of the Due Boemi also newly discovered music from the

Renaissance period (suites of dances and songs by anonymous

composers of the 15th, 16th and 17th century), barocs

sonatas for a deep melody instrument and basso continuo (like Händel,

Telemann, Purcell, Marcello and others). In addition, seldom heared

classic a romantic pieces of Mozart, Beethoven, Dvořák,

Smetana, Schumann, and indeed, there are great many for the Due

Boemi di Praga specially composed, dedicated ot authorized

contemporary opus of different styles.

|

|

| |

22 June 2005

In Memoriam David Breeden

- Solo Clarinetist with San Francisco Symphony

San

Mateo, California USA

David Breeden, 58, Solo

Clarinetist in the San Francisco Symphony, died June 22 of complications from

multiple myeloma at a care center in San Mateo, California.

Mr. Breeden is the son of

Leon Breeden, the former Grand Prairie High School band director who went on to

be the longtime head of jazz studies at what is now the University of North

Texas.

David Breeden was born in

Fort Worth. He and his family later lived in Grand Prairie and Denton as his

father's career progressed. David Breeden followed in his father's footsteps to

play the clarinet. The retired professor said his son was a natural.

When David was in fourth

grade, he heard his father practicing and told him he liked the sound. Mr.

Breeden told his son that he would give him a clarinet if he learned to play. He

heard his answer six weeks later.

"I walked in our little house

there in Grand Prairie one afternoon after band rehearsal, and I heard

'Stardust' going in the front room," Mr. Breeden said. "I said, 'David, that

horn is yours.' "

David Breeden received

degrees from North Texas State University, now UNT, and Catholic University. He

performed for several years with the Navy Band before joining the San Francisco

Symphony in 1972.

17 February 2005

Munich, Germany - In memoriam

Marcello Viotti

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Marcello Viotti, an Italian conductor with

strong Swiss roots (www.marcello-viotti.com)

|

|

|

|

Swiss-born

conductor Marcello Viotti, musical director of Venices La

Fenice Theatre, has died at the age of 50.

Viotti conducted

renowned orchestras, including the Berlin Philharmonic, New

Yorks Metropolitan Opera and the English Chamber Orchestra,

and performed at opera houses around the world. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Viotti died on

Wednesday in a Munich hospital after suffering a stroke last

week.

Born to Italian immigrants in western Switzerland in 1954,

Viotti studied the piano, cello and singing at the Lausanne

Conservatory. He made his conducting debut in nearby Geneva with

a wind ensemble that he founded in 1974.

In 1982 he won first prize at a renowned conducting competition

in Italy, which launched his international career.

He rose to prominence as chief conductor of the Turin Opera.

Viotti served as artistic director of the Lucerne Theatre in

Switzerland and conducted orchestras in several German cities.

Last year he quit his position as conductor in Munich in protest

at plans to shut down the orchestra in 2006. Viotti had notably

directed a successful concert cycle with Munichs Radio

Orchestra, entitled Paradisi Gloria, devoted to

20th-century choral music.

Venice, New York,

Vienna

At Venices La

Fenice Theatre, where he had been musical director since 2002,

Viotti won acclaim for his production of Jules Massenets

Thais.

Other productions included Giuseppe Verdis La Traviata

and Richard Strausss Ariadne auf Naxos.

Viotti made his debut at the Met in New York in 2000 with

Giacomo Puccinis Madame Butterfly. He later returned

for La Bohème and La Traviata.

He gave his last public performance on February 5, when he

conducted Vincenzo Bellinis Norma at the Vienna State

Opera.

Viotti was due to conduct new productions in Venice, Salzburg

and Zurich later this year.

The world of music praised Viotti as a leading light of his

generation.

"He will live on not only because of his high professional

standard and his musical talents, but also his warm personality

and generosity," said Alexander Pereira, director of Zurichs

Opera House. |

|

|

|

|

|

Portrait

by Donna Granata

Emily Bernstein

in Memoriam (1959 - 2005)

At the time of her death, Emily Bernstein was the principal clarinetist of the

Los Angeles Opera. She also played first chair with the Pasadena Symphony under

the direction of Jorge Mester. She was a member of the acclaimed contemporary

music ensemble, XTET, which has presented numerous world premieres. She

performed with many southern California ensembles including the Angeles String

Quartet, and the Pacific Trio. She enjoyed many happy summer seasons in

Jacksonville, Oregon as principal clarinetist with the Peter Britt Music and

Arts Festival. In addition to her busy performing career, Emily maintained an

active private teaching studio and was affiliated with the Mancini Institute.

Ms.

Bernstein graduated with honors from Stanford University and earned a Master of

Music degree from the Eastman School of Music.

Ms.

Bernstein made frequent appearances as a soloist and chamber musician throughout

the west and recorded for the Delos, Phillips, and Sony Classics labels. She was

an active studio musician and has performed on hundreds of motion picture and

television scores including, Catch Me If You Can, Pirates of the Caribbean, Sea

Biscuit, and JAG. She was featured in the John Williams score for the movie The

Terminal. An article in the La Cañada Valley Sun reported that after Emily

recorded the clarinet solo for "The Terminal," director Steven Spielberg - a

former clarinetist himself - insisted that Bernstein's name appear in the film's

end credits, although traditionally individual musicians performing in studio

orchestras remain anonymous.

2 January 2005

Raleigh, North Carolina USA - Herbert Blayman - in Memoriam

The Clarinet world lost a hallmark Clarinetist and teacher in Mr Blayman, an

established artist-teacher and celebrated Solo Clarinetist in the Metropolitan

Opera Orchestra at Lincoln Center in New York. As a pedagogue, he taught

at the Manhattan School of Music and other schools in New York and has been

responsible for the effective mentorship of students who have achieved major

successes in the music performance field. Since retiring from the Orchestra, he

has pursued Clarinet mouthpiece making with an incredible quality control played

by many professionals around the USA. Blayman stands as one of the rare

teachers who have left a benchmark to be emulated in this generation.

30 December 2004

Artie Shaw in Memoriam

|

The

following biography was written in September of 1995. Artie Shaw was 94. |

|

On

the eve of America's entry into World War II, TIME magazine reported that to

the German masses the United States meant "sky-scrapers, Clark Gable, and

Artie Shaw." Some 42 years after that, in December l983, Artie Shaw made a

brief return to the bandstand, after thirty years away from music, not to

play his world-famous clarinet but to launch his latest (and still touring)

orchestra at the newly refurbished Glen Island Casino in New Rochelle, New

York.

Oddly

enough, New Rochelle isn't all that far from New Haven, Connecticut, where

Artie Shaw spent his formative years and at an early age became a compulsive

reader, and where at 14 he began to play the saxophone (and several months

later the clarinet), and at 15 left home to play all over America, and

meanwhile study the work of his early jazz idols, such as Bix Beiderbecke,

Frank Trumbauer, and Louis Armstrong. |

|

|

At the age of 16 Artie

went to Cleveland, where he remained for three years, the last two working

with Austin Wylie, then Cleveland's top band leader, for whom Shaw took over

all the arranging and rehearsing chores. In 1927 Artie heard several "race"

records, the kind then being made solely for distribution in black (or

"colored," as they were then known) districts. After listening entranced to

Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five playing Savoy Blues, West End

Blues, and other now-classic Louis Armstrong records from the late

1920's, Artie made a pilgrimage to Chicago's Savoy Ballroom to hear the

great trumpet player in person. Back in Cleveland, Artie, now 17, won an

essay-writing contest which took him out to Hollywood in 1928, where he ran

into a couple of musicians he had known back in New Haven who were now

working in Irving Aaronson's band. A year later, at the age of 19, Artie

moved to Hollywood to join the Aaronson band.

Shortly

afterwards, the Aaronson band spent the summer of 1930 in Chicago, where

Artie "discovered a whole new world" (as he would much later write, in a

semi-autobiographical book The Trouble With Cinderella first

published in 1952) when he heard several recordings of some of the then

avant-garde symphonic composers' work: Stravinsky, Debussy, Bartok, Ravel,

et al, whose work would eventually influence most of our contemporary jazz

performers. This influence would soon surface in Shaw's own work when he

began to use strings, woodwinds, etc. -- notably in a highly unusual album

entitled Modern Music for Clarinet, selections of which were also

featured in several of Shaw's Carnegie Hall concerts.

When

the Aaronson band came to New York in 1930, Artie decided to stay there, and

within the year, at age 21, he became the top lead-alto sax and clarinet

player in the New York radio and recording studios. After a couple of years

of commercial work, he became disillusioned with the music business and

bought some acreage with an old farmhouse in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. He

moved out there to spend the next year chopping wood for a living and trying

to train himself as a writer -- of books rather than music -- since there

seemed to be no way at that time to make a decent living playing the kind of

music that interested him.

In

1934 he returned to New York to pick up his formal education where it had

been abruptly terminated when he left high school at 15, and resumed studio

work to support himself. He made his first public appearance as a leader in

1936, in a Swing Concert (history's first) held at Broadway's Imperial

Theatre. This proved to be a major turning point in his career, and would in

fact ultimately have a significant impact on the future of American Big Band

jazz. Shaw (who was then completely unknown to the general public) did

something totally unorthodox to fill one of the three minute interludes in

front of the stage curtain while such then established headliners as Tommy

Dorsey, the Bob Crosby Band, the Casa Loma Band, etc. were being set up.

Instead of the usual jazz group (a rhythm section fronted by a soloist),

Shaw composed a piece of music for an octet consisting of a legitimate

string quartet, a rhythm section (without piano), and himself on clarinet --

an extremely innovative combination of instruments at that time. Fronting

this unusual group, he played a piece he had written expressly for the

occasion, Interlude in B-flat, which the group presented to a totally

unprepared and, as it turned out, wildly enthusiastic audience. (This, by

the way, is the first example of what has now come to be labeled "Third

Stream Music.")

Shaw

could scarcely have known that within a short time he would make a hit

record of a song called Begin the Beguine, which he now jokingly

refers to as "a nice little tune from one of Cole Porter's very few flop

shows." Shortly before that he had hired Billie Holiday as his band vocalist

(the first white band leader to employ a black female singer as a full-time

member of his band), and within a year after the release of Beguine, the

Artie Shaw Orchestra was earning as much as $60,000 weekly -- a figure that

would nowadays amount to more than $600,000 a week!

The

breakthrough hit record catapulted him into the ranks of top band leaders

and he was immediately dubbed the new "King of Swing". Today, Shaw's

recording of Begin the Beguine sells thousands and has become one of

the best-selling records in history.

Superstardom

turned out to be a status that Shaw (as a compulsive perfectionist) found

totally uncongenial. Within a year he abruptly took off for another respite

from the music business, this time in Mexico. In March of 1940 he re-emerged

with a recording of Frenesi, which became another smash hit. For this

recording session, he used a large studio band with woodwinds, French horns,

and a full string section along with the normal dance band instrumentation

-- another first in big band jazz history. Later that year he formed a

touring band with a good-sized string section, with which he recorded

several more smash hits, among them his by now classic version of Star

Dust, plus a number of other fine musical recordings such as Moonglow,

Dancing in the Dark, Concerto for Clarinet, and many others.

Shortly

after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the unpredictable Shaw quit the music

business once again, this time to enlist in the U.S. Navy. After finishing

boot training, he was asked to form a service band which eventually won the

national Esquire poll. He spent the next year and a half taking his music

into the forward Pacific war zones, playing as many as four concerts a day

throughout the entire Southwest Pacific, on battleships, aircraft carriers,

and repair ships, ending with tours of Army, Navy, and Marine bases (and

even a number of ANZAC ones when his band arrived in New Zealand and

Australia). On returning to the U.S. -- after having undergone several

near-miss bombing raids in Guadalcanal -- physically exhausted and

emotionally depleted, he was given a medical discharge from the Navy. His

troubled marriage to Betty Kern (the daughter of composer Jerome Kern) ended

in divorce, and in 1944 Shaw formed another civilian band -- featuring such

great performers as pianist Dodo Marmarosa, guitarist Barney Kessel, and the

phenomenal trumpeter Roy Eldridge -- with which he toured the country and

made many excellent recordings.

In

1947, during another hiatus, Shaw spent about a year in New York City in an

intensive study of the relation of the clarinet to non-jazz (or, as he

prefers to call it, "long-form") music. This culminated in a tour in 1949 of

some of the finest musical organizations in America, such as the Rochester

Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Eric Leinsdorf, the National

Symphony in Washington, D.C., the Dayton Symphony, three appearances with

New York's "Little Orchestra" (one in Newark, a second in Brooklyn's Academy of

Music, and the last in Town Hall). After that Shaw recorded the

aforementioned Modern Music for Clarinet album, containing a

collection of remarkably well crafted symphonic orchestrations of short

works by Shostakovich, Debussy, Ravel, Milhaud, Poulenc, Kabalevsky,

Granados, Gould, along with Cole Porter and George Gershwin. About that time

Shaw again appeared in Carnegie Hall, as guest soloist with the National

Youth Orchestra conducted by Leon Barzin, where he received critical acclaim

for his rendition of Nicolai Berezowski's formidable Concerto for

Clarinet, which he had previously presented in its world premiere a few

weeks earlier with the Denver Symphony. Around that time he performed the

Mozart Clarinet Concerto with the New York Philharmonic conducted by

Leonard Bernstein at a benefit performance, held at Ebbetts Field, for

Israel's Philharmonic Orchestra.

During that year, Shaw also played numerous chamber music recitals with

string quartets, at various colleges and universities around the country.

Another

of Shaw's ventures during that period was his great 1949 band, which was

virtually ignored by the general public until 1989, when an album of some of

its work was released on compact discs by MusicMasters, and has since

received remarkable worldwide reviews.

In

1951 Shaw again quit the music business, this time moving to Duchess County,

New York, where he bought a 240 acre dairy farm and wrote his first book, a

semi-autobiographical work entitled The Trouble With Cinderella: An

Outline of Identity, sections of which have appeared in many

anthologies, and which is still in print.

Throughout

the early fifties, Artie Shaw assembled several big bands and small combos

-- as well as his own symphony orchestra, (to play a one-week engagement at

the opening of a large New York jazz club called Bop City). One such combo which

was formed in late 1953 and recorded in 1954, a group known as the Gramercy

5 (a name he took from the New York telephone exchange of the time),

maintain an amazingly high degree of popularity to this day despite the

onslaught of Rock, MTV, and other such commercial phenomena.

In

1954 Artie Shaw made his last public appearance as an instrumentalist when

he put together a new Gramercy 5 made up of such superb modern musicians as

pianist Hank Jones, guitarist Tal Farlow, bassist Tommy Potter, et al. The

most comprehensive sampling of that group (as well as a number of others,

going all the way back to 1936 and on up through this final set of records)

can be heard on a four record album, now a rare item, released in 1984 by

Book of the Month Records, entitled: Artie Shaw: A Legacy, which has

also received rave reviews. Some of this music was re-issued on two double

CD's by MusicMasters as Artie Shaw: The Last Recordings, Rare and

Unreleased, and Artie Shaw: More Last Record�ings, The Final Sessions.

Artie

Shaw packed his clarinet away once and for all in 1954. In 1955 he left the

United States and built a spectacular house on the brow of a mountain on the

coast of Northeast Spain, where he lived for five years. On his return to

America in 1960 he settled in a small town named Lakeville, in northwestern

Connecticut, where he continued his writing, and in 1964 finished a second

book (consisting of three novellas) entitled I Love You, I Hate You, Drop

Dead! In 1973, he moved back to California again, finally ending up in

1978 in Newbury Park, a small town about 40 miles west of Los Angeles,

situated in what he refers to as "Southern California pickup-truck country."

Since

then, aside from a brief venture into film distribution (1954 to 1956), and

a number of appearances on television and radio talk shows, Artie Shaw has

had very little to do with music or show business. He still gives occasional

interviews on television, radio, and newspapers and lectures all over the

United States. He still conducts seminars on literature, art, and the

evolution of what is now known as the Big Band Era. He has given lectures at

Yale University, the University of

Pennsylvania, the University

of Southern California, the

University of California at Santa Barbara,

the California State University at Northridge, and Memphis State University.

He has received Honorary Doctorates at California Lutheran University and

the University of Arizona. His home contains a library of more than 15,000 volumes, including a

large collection of reference works on a wide variety of subjects ranging

from Anthropology to Zen.

Artie

Shaw has been a nationally ranked precision marksman, an expert

fly-fisherman, and for the past two decades has been working on the first

volume of a fictional trilogy, dealing with the life of a young jazz

musician of the 1920's and 30's whose story he hopes to take on up into the

1960's.

Shaw's

own life is the subject of a fine feature-length documentary by a Canadian

film-maker. Artie Shaw: Time Is All You've Got is a painstakingly

thorough examination of Shaw as he is today and as the leader of some of his

great bands, including an appearance from one of his two earlier motion

pictures, Second Chorus (1940). (Scenes from his other motion

picture, Dancing Coed (1939), were not included in the documentary

due to prohibitive cost.) In a review of the film at Los Angeles's Filmex

Film Festival in the summer of 1985, Variety commented: "A riveting

look back at both the big band era and one of its burning lights." The film

has received glowing reviews wherever it has been shown -- Los Angeles,

Santa Barbara, Minneapolis, Toronto, Boston, and on Cinemax -- as well as in

England, where it ran twice on BBC. It has also appeared at Film Festivals

in Belgium, Switzerland, Australia, and Spain (where it took first prize in

the documentary category). In 1986 it opened the San Francisco Film

Festival, and in 1987 the Academy of

Motion Picture Arts and

Sciences awarded it the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature of 1986.

On

first meeting Artie Shaw, young Wynton Marsalis remarked, "This man's got

some history." Shaw is regarded by many as the finest and most

innovative of all jazz clarinetists, a leader of several of the greatest

musical aggregations ever assembled, and one of the most adventurous and

accomplished figures in American music.

As

Artie Shaw goes on into his nineties, he has also developed a crusty humor,

as evidenced by an epitaph for himself he wrote for Who's Who in America a

few years ago at the request of the editors: "He did the best he could with

the material at hand." However, at a recent lecture to the music students of

the University of Southern California, when

someone mentioned having read it, Shaw said, "Yeah, but I've been thinking

it over and I've decided it ought to be shorter, to make it more elegant."

And after a brief pause, "I've cut it down to two words: 'Go away.'"

|

|

|

7 December 2004

Siesta, Florida USA - In Memoriam Frederick Fennell

|

In Memoriam

Maestro Frederick

Fennell

Principal Guest Conductor, Dallas

Wind Symphony

July 2, 1914

- December 7, 2004

Dr. Frederick Fennell passed

away peacefully at his home in Florida on December 7.

The maestro served as

Principal Guest Conductor of the

Dallas Wind Symphony

for many years and we are profoundly saddened by

this loss. The band world has

truly lost one of its greatest. Our prayers go out

to him and his family.

Home -

People |

|

Dr. Frederick

Fennell is one of the world's most active and innovative maestros.

This globe-trotting nonagenarian is principal guest conductor of the

Dallas Wind Symphony, principal conductor of the Tokyo Kosei Wind

Orchestra in Japan, and Professor Emeritus at the University of

Miami School of Music.

The

internationally-acclaimed conductor is widely regarded as the leader

of the wind ensemble movement in this country, is one of America's

most recording living American classical conductors, and is a

pioneer in various methods of recording.

While

maintaining obvious devotion to the band and its music, he has

pursued such illustrious and wide ranging activities as conductor of

orchestra, opera, and popular repertoire. He has made guest

conducting appearances with symphony orchestras and bands all over

the world, is a member of many organizations, and has won numerous

awards.

Born July 2, 1914 in Cleveland,

Ohio, the maestro studied at the Eastman School of Music on the

University of Rochestrer campus, earning a Bachelor of Music degree

in 1937 and a Master of Music degree two years later. He became a

member of the Eastman conducting faculty in 1939, founded the

Eastman Wind Ensemble in 1952, and received an Honorary Doctorate

from Eastman in 1988.

High-fidelity

and stereo performances on 22 albums for Mercury Records grant him a

unique position in the annals of the recording art. He was conductor

of the Cleveland Symphonic Winds when he made the first symphonic

digital recording in the United States for Telarc Records in 1978.

The maestro also pioneered high definition compatible digital (HDCD)

recordings with the Dallas Wind Symphony. The maestro has also

recorded for CBS-Sony, Nippon-Columbia, King and Kosei labels.

Dr. Fennell has

served as conductor of the Columbia University American Festival,

the National Music Camp, the Yaddo Music Period, the

Eastman-Rochester Pops Orchestra and the Eastman Opera Theatre,

among others.

He has been

principal guest condluctor of the Interlochen Arts Academy, and

other guest conducting stints include frequent appearances with the

Boston Pops Orchestra as well as performances with the Carnegie Hall

Pops Concerts and the Boston Esplanade concerts. He has appeared

with the Denver, San Diego, National, Hartford, St. Louis and London

Symphonies; the Buffalo, Calgary and Greater Miami Philharmonic

Orchestras, the Cleveland Orchestra and the New Orleans

Philharmonic.

He was also

previously Musical Director of the School Orchestra of America with

which he toured Europe in the mid '60s.

Through the years, Dr. Fennell has risen to legendary

stature in the world of music and this is reflected in the honors

bestowed upon him. These include an Honorary Doctor of Music degree

from

Oklahoma City University, membership in the Society of the Sons of

the American Revolution, honorary chief status in the Kiowa tribe,

and a fellow in the Company of Military Historians.

In 1961, he

received a citation and a medal from the Congressional Committe for

the Centennial of the Civil War for two volumes of recordings of the

Music of the Civil War.

Also, he was the

recipient of the 25th Anniversary of Columbia University Ditson

Conductor's Award in April of 1969, and of the New England

Conservatory's Symphonic Wind Ensemble Citation in 1970. He was also

awarded the Mercury Record Corporation Gold Record in 1970, and the

National Academy of Wind and Percussion Arts Oscar for outstanding

service as a conductor in 1975.

The

Fennell/Eastman Wind Ensemble recording of Percy Grainger's

Linconshire Posy was selected as one of the Fifty Best Recordings of

the Centenary of the Phonograph, 1877-1977, by the Stereo Review. In

1977, he was named consultant to the Scala Memorial Fund Library of

Congress. That same year, he received the Eastman School of Music

Alumni Citation for the 25th Anniversary of the founding of the

Eastman Wind Ensemble.

He received the

University of Rochester Outstanding Alumni Award in 1981, and the Kappa Kappa Psi Distinguished Service

Medal in 1982.

He was presented

the Star of the Order in 1985 from the John Philip Sousa Memorial

Foundation.

Other

distinctions include the Interlochen Medal of Honor and the Midwest

International Band and Orchestra Clinic Medal of Honor, awarrded in

1989. The following year, Dr. Fennell was inducted into the National

Bandmasters Association Hall of Fame for Distiguished Band

Conductors. In January of 1994, he received the Theodore Thomas

Award presented by the Conductors Guild, Inc., in recognition of

unparalleled leadership and service to windband performance

throughout the world. The last two recipients of this award were

maestros Solti and Bernstein.

He was the

initial recipient of the Medal of the International Percy Grainger

Society for Distinguished Services in 1991.

Frederick

Fennell Hall was dedicated in Kofu, Japan,

with a concert by the Tokyo Kosei Wind Orchestra on July 17, 1992.

Dr. Fennell has

authored several publications with musical topics, including his

1954 book Time and the Winds, which is still the only text of its

kind. He is also the author of the continuing series The Basic Band

Repertory Study/Performance Essays, editor of contemporary editions

of classic military, circus and concert marches for Theodore Presser

Co., Carl Fisher, Inc., Sam Fox Publishing Co., Boosey & Hawkes,

Inc., and of the Fennell Editions for Ludwig Music. |

|

| |

| |

30 June 2004

Risei Kitazume (1919-2004) - In

Memoriam -

Tokyo, Japan

Risei Kitazume, past president of Japan Clarinet Society from 1980 to

1986, died of pancreatic cancer on June 30, 2004. HI is survived by his wife

Waki, his parents and his children, Michio and Yayoi both of them are composers.

Mr. Kitazume was born in the mid of Tokyo on April 16, 1916 and started

playing trumpet in 1929 when he entered Sijyo junior high school. In 1934, he

began to play clarinet at Seijyo High School under the instruction of Mr. Tomio

Tsujii and Mr. Tetsuo Yamamura. He received his undergraduate degree of music

from Tokyo Music School (now called Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and

Music) in 1941. His mentor was Mr. Hironori Nakayama. He was awarded Koda grant.

He served military from February 1942 to August and he resigned because of his

health. After returning from military service he completed his graduate school

and assigned as a part-time lecture of the school. In the same year, he married

with his wife. In 1942 he joined Tokyo Broadcasting Symphony Orchestra and from

1945 he again served military till the end of the World War II. In 1946 he moved

to Tokyo Philharmonic and also assigned as an associate professor of Tokyo

National University of Fine Arts and Music. In 1947 he moved to Toho

Philharmonic (now called as Tokyo Symphony Orchestra). He also played with

Eolian Club with Hidemaro Konoe. From 1955, he was assigned as an associate

professor of Toho Gakuen and then a full professor and he received an honorary

professor in 1997 and also he taught several schools including Yamagata

University, Senzoku Gakuen, Nihon University, Soai Gakuen, and so on. Beside

those teaching careers, in 1965 he introduced the Krommer Clarinet Concerto #1

and played with Tokyo Symphony Orchestra and Mr. Kazuyoshi Akiyama as a

conductor, and Olivier Messiaen's Quatuor Pour La Fin Du Temps (Quartet For The

End Of Time) in 1967.

Mr. Kitazume gave much to this society through his teaching and performing

and we regret that he did not have more time among us.

29 June 2004

Jost Michaels - in Memoriam

Detmold,

Germany

|

Jost Michaels, clarinetist, pianist, conductor, writer and arranger

died on June 21st at the age of 82, after a long illness. I had the

privilege of studying with Prof. Michaels in Detmold from 1980 to 1983

and worked with him subsequently on the Boehm-System version of his

legendary Systematic of Clarinet Fingering Technique. He was one of

the few musicians I have ever met. He played piano and

clarinet and was one of the only people ever to receive a double

professorship in both instruments in Germany. He recorded extensively

on both instruments, published many articles on musical subjects and

arranged numerous works for clarinet. He was also quite proficient on

the violin.

Professor

Michaels was uncompromising in his desire to bring out the best of

every piece he played. He was a champion of unknown composers and

their works, believing that one cannot understand the greatness of

masterpieces if one does not have a thorough knowledge of the other

works of their time, and of the composers who, from our point of view,

stand almost hidden in the shadows of the masters.

Jost Michael's students

sit in major international orchestras and teach at institutions all

over the world. He taught in a way that went far beyond instruction in

tone and technique. He taught each student to use their own sound and

abilities to get to the heart of a compositionâs musical character,

and to be able to lead listeners to understand the intensity,

structure and special character of each piece. He was insistent on

players knowing the whole piece, and not just the clarinet part, on

their knowing as many other pieces by the same composer - and all his

or her contemporaries! - as possible. I have seen him practically

throw students out of lessons if they didnÌt know if a composer had

written Lieder (Art Songs) or not. A prerequisite for any lesson was

knowing the piano part inside and out, as he accompanied all lessons

himself and had little patience for wrong tones or entrances...I think

you better take another look at this, Herr .....!

At the end of his teaching career he

packed the clarinet away and dedicated himself more to piano and even

more to research and writing. Near the end of his life he published

two works of importance. The Dilemma in Modern Musical Education,

about the need for restructuring musical education to meet purely

artistic needs, and to increase the students ability to interpret

unknown (unrecorded) works. His last work was a major treatise on

Brahms use of the clarinet, asserting and evaluating Brahms

relationship to the clarinet before his friendship with Muhlfeld.

I will miss Jost

Michaels. He demonstrated what it is like to be totally immersed with

mind and spirit in what one is playing. He was also a window into

another epoch of music-making, if you will, having studied with

masters from the 19th century, and being a product of early 20th

century ideas. The most modern-day musician still has a need for

hearing âold-timeâ ideas to be truly equipped for the music at

hand. For me, and many other of his students, the intensity of Jost

Michaels music-making and teaching awakened that part of me

which could play the best.

Allan Ware |

|

June 2004

John LaPorta -

in Memoriam

New York City USA

John LaPorta (1920-2004) was classically trained in part at the Manhattan School

of Music and joined the Bob Chester band in 1940 to play lead clarinet. He

worked with Ray McKinley and Woody Herman as an alto saxophonist and composer.

He took over Buddy DeFranco's spot with the Metronome All-Stars in 1951 (as a

clarinetist) and was a founding member of the Jazz Composer's Workshop (with

Charles Mingus and Teo Macero) in 1953. He recorded extensively with Mingus,

the JCW, and Lennie Tristano in the 1950s on both sax and clarinet. He wrote

articles for Downbeat magazine including "Up Beat Section: Clinician's Corner"

about learning to play jazz in 1960. He also recorded under his own name on

the albums "John LaPorta", "Conceptions", "Clarinet Artistry", and "Most

Minor". He was a jazz educator starting in the 1950s and served on the faculty

at the Manhattan School of Music (1959-1980s). His playing and arranging was

widely respected by modern jazz players in the 1950s and 1960s and helped found

jazz education.

|

|

|

|

Stanley Drucker with Jean and David Hite on mouthpieces

|

|

|

|

Drucker- Hite mouthpiece tryouts

|

|

|

|

Stanley Drucker with Hite mouthpiece check

|

|

|

|

Hite Mouthpiece session

|

|

|

18 January 2004

David Hite - in Memoriam

Estero, Florida USA

David Hite, age 80, a resident

of Estero FL, died Sunday, January 18, 2004 at Hope Hospice, Ft. Myers FL. He

had been taken ill suddenly four weeks earlier. Born Sept. 25, 1923 in New

Straitsville OH, he devoted his life to the study and mastery of the clarinet.

He studied with Fred Weaver of Columbus, Daniel Bonade of New York, and Anthony

Gigliotti of Philadelphia. After moving with his family to Columbus in 1941, he

enrolled in the Ohio State University School of Music where he subsequently

earned Bachelor and Master of Arts Degrees in Music. During WWII he joined the

US Army, serving in Guam and Okinawa as a band musician. Upon discharge, he

returned to play in the Columbus Philharmonic Orchestra and in the Berkshire

Music Festival Orchestra at Tanglewood MA. In 1954 he joined the music faculty

of Capital University where he taught for over 20 years. In 1980, he joined in

collaboration and support of the Klar/Fest 81 at Catholic University and was

instrumental in the success of this Festival and several subsequent Clar/Fests

in Washington and Towson State Universities. ClariNetwork International

was organized at this time after the artistic success of the Klar/Fest.

After leaving Columbus in 1983, he moved to the New York City area, working with

artist clarinet and saxophone players in custom servicing instruments and

mouthpieces. In 1986 he settled in Florida where, with his wife Jean, he won

international recognition for the design and production of

J & D Hite clarinet

and saxophone mouthpieces. He also worked to expand the clarinet music

literature, publishing many new editions and arrangements with Southern Music

Company. Survived by wife Jean Ann Knox Hite; son Christopher (Angela) Hite and

grandson Benjamin Hite of Annandale VA; son Mark D. Hite of Columbus. Preceded

in death by parents Harry and Dollie Hite, brother Lester, and sister Hazel.

Arrangements in care of the National Cremation Society, 12820 Kenwood Lane, Ft

Myers, FL 33907. In lieu of flowers, the family requests that donations in

Davids memory by made to a charity of the donors choice or the

Ft. Myers, FL foundation which David supported: The Music Foundation of

Southwest Florida

13300-56 S. Cleveland Ave.,

PMB-214

Ft. Myers, FL 33907

http://www.music-foundation.org/

December 17, 2003

Henry Cuesta - in Memoriam

Los Angeles, California USA -

Henry Cuesta, highly

regarded star clarinetist best known as a featured musician with the

Lawrence Welk Orchestra, his technical mastery of the clarinet was often

compared to that of Benny Goodman. He performed with the Lawrence Welk